|

|

||||||||||||

|

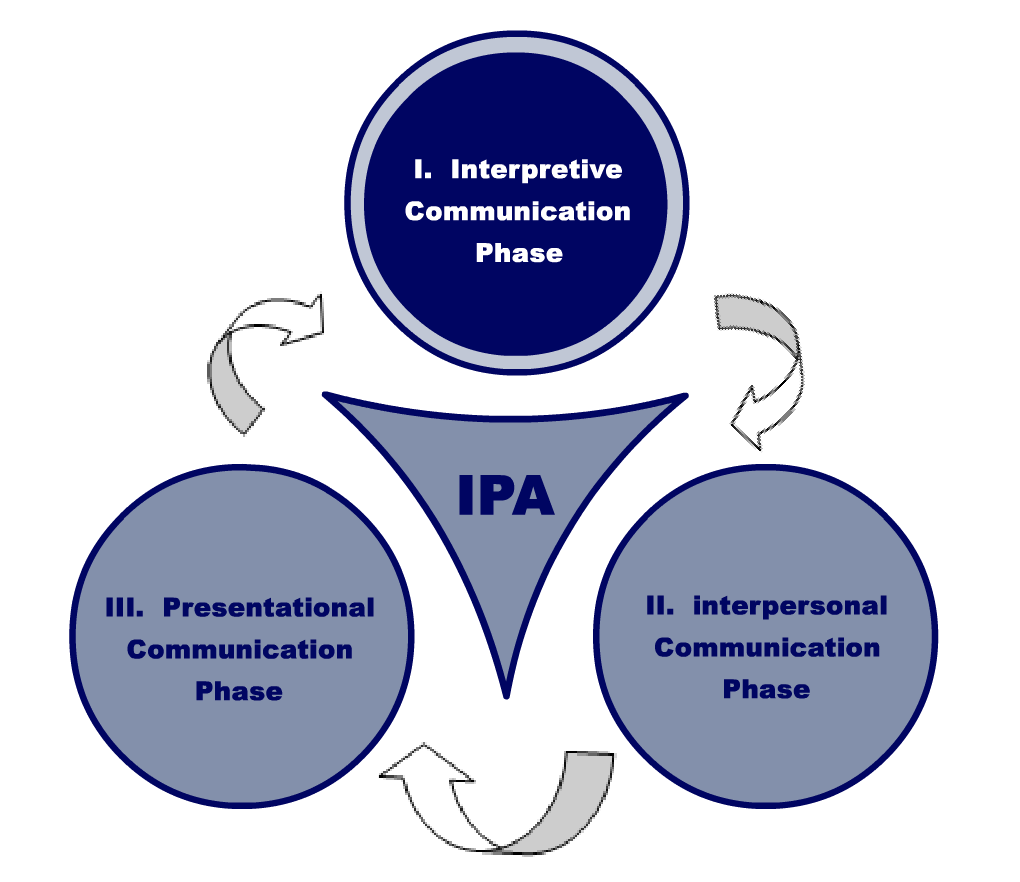

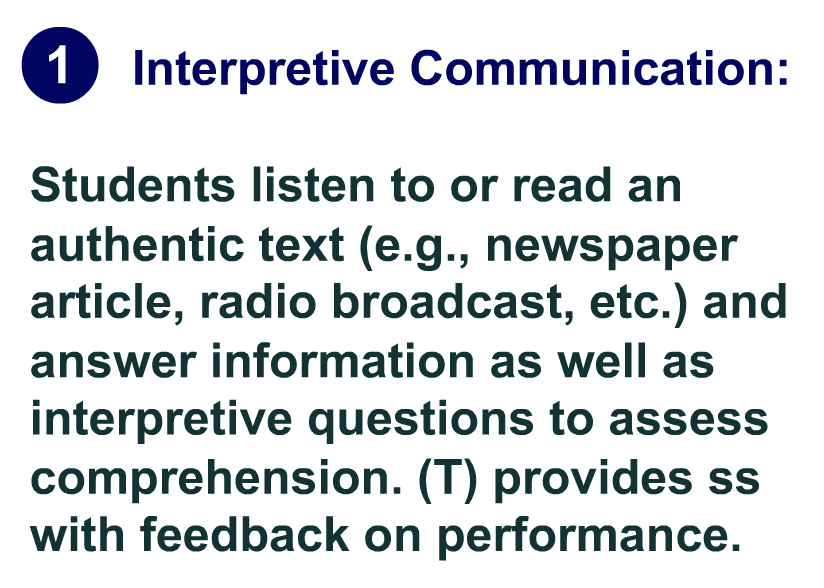

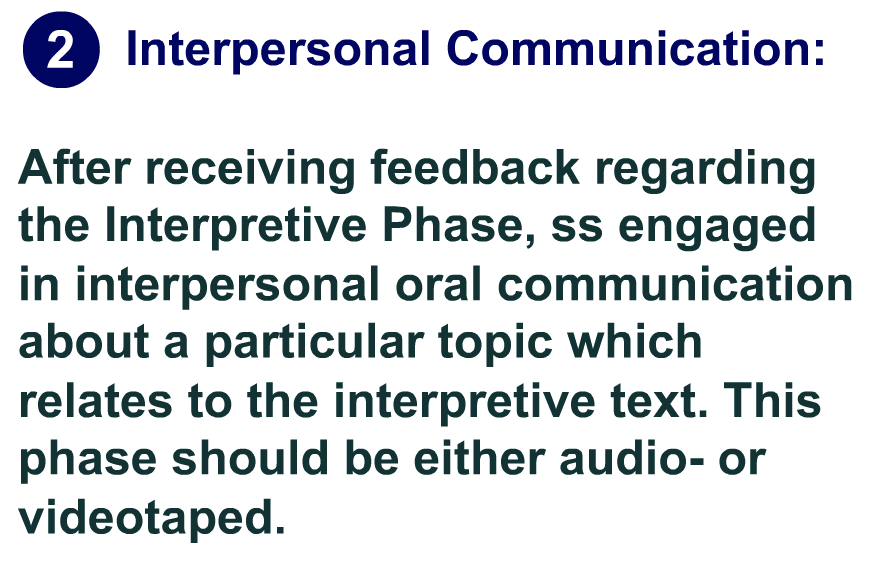

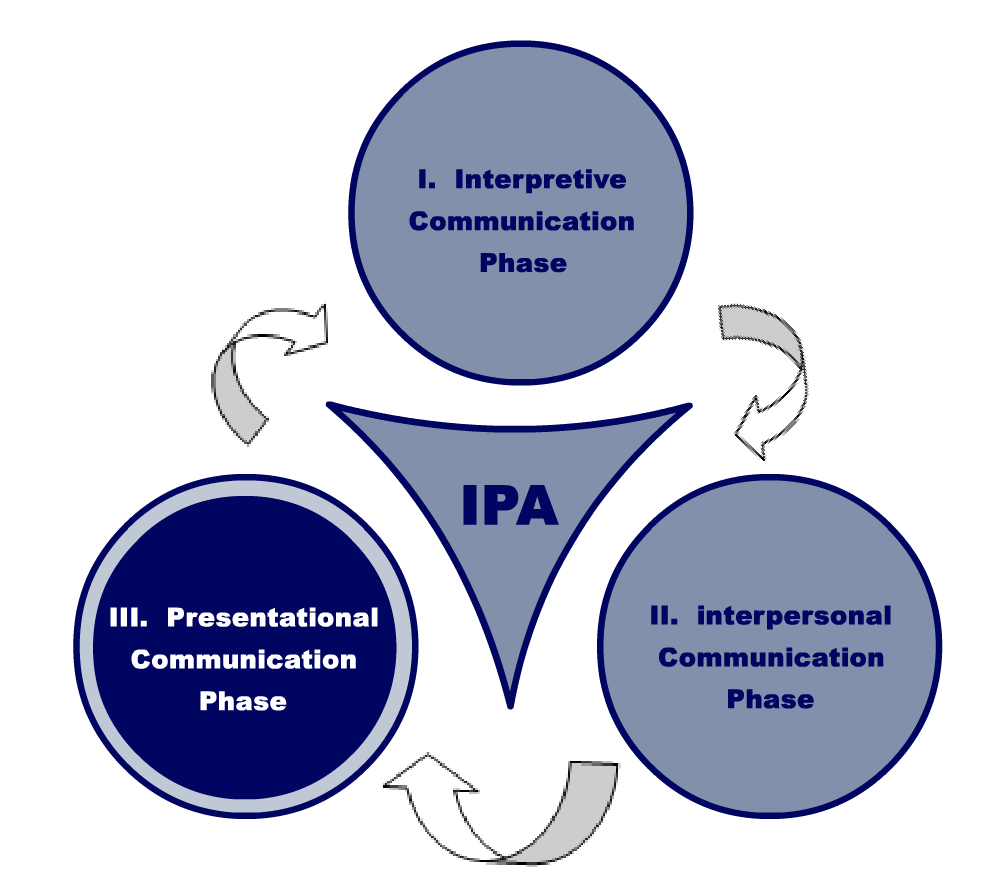

Integrated Performance Assessment: D. Tedick & L. Cammarata In CBI, learners are held accountable for both CONTENT and LANGUAGE learning. This means that the assessment tasks and assessment tools (e.g., rubrics) that are developed for CBI must address both. Assessment can take a variety of forms in CBI, but the most valuable types of assessment tasks are those that require students to use language meaningfully to demonstrate what they’ve learned about the content. For example, culminating synthesis tasks (Stoller, 2002), such as oral presentations or written reports, are often a good choice for summative assessment in CBI–they require students to be actively engaged and guide them in consolidating content learning while using language in meaningful ways. Project-based learning (PBL) also serves as a valuable approach to assessment in CBI. PBL is defined as interaction wherein students are socialized via individual and group activities that require language and content learning through planning, researching, analyzing, and synthesizing data (Beckett & Slater, 2005). Another framework that may also inform assessment for CBI is the Integrated Performance Assessment (IPA) model developed by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) (Glisan et al., 2003). The IPA was not originally developed to serve as an assessment approach for CBI, rather its primary focus is on assessing language only. However, we find the IPA to have tremendous potential for CBI as long as a number of key modifications are made. What is the IPA? In a nutshell, the IPA is a classroom-based assessment model that can be used for evaluating student’s language use in the three communicative modes (interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational) that correspond to the communication standards that appear in the national Standards for Foreign Language Learning (1996/1999). In its original form, the IPA model proposes a cyclical approach to the development of performance assessment units. These units are designed around a major theme and are composed of tasks that correspond to the three principal modes of communication. Backward design is presented as a key component in the process of creating IPA units. The process begins with the three communicative modes as a reference point, and then moves to the selection of a theme followed by the creation of tasks around that theme, which correspond to the three modes. For example, within the theme of food and nutrition, students might read about and study a diagram of the new food pyramid for the interpretive task. Then for the interpersonal task, they might be assigned to a partner and be asked to compare a food diary in the context of what they learned about the food pyramid and daily dietary guidelines. Finally, for the presentational task students might create a daily food plan and explain orally to the class how their menu corresponds to the food pyramid guidelines. Figure 1 provides an overview of the assessment cycle. For a more detailed description and several examples, see CARLA’s Virtual Assessment Center.

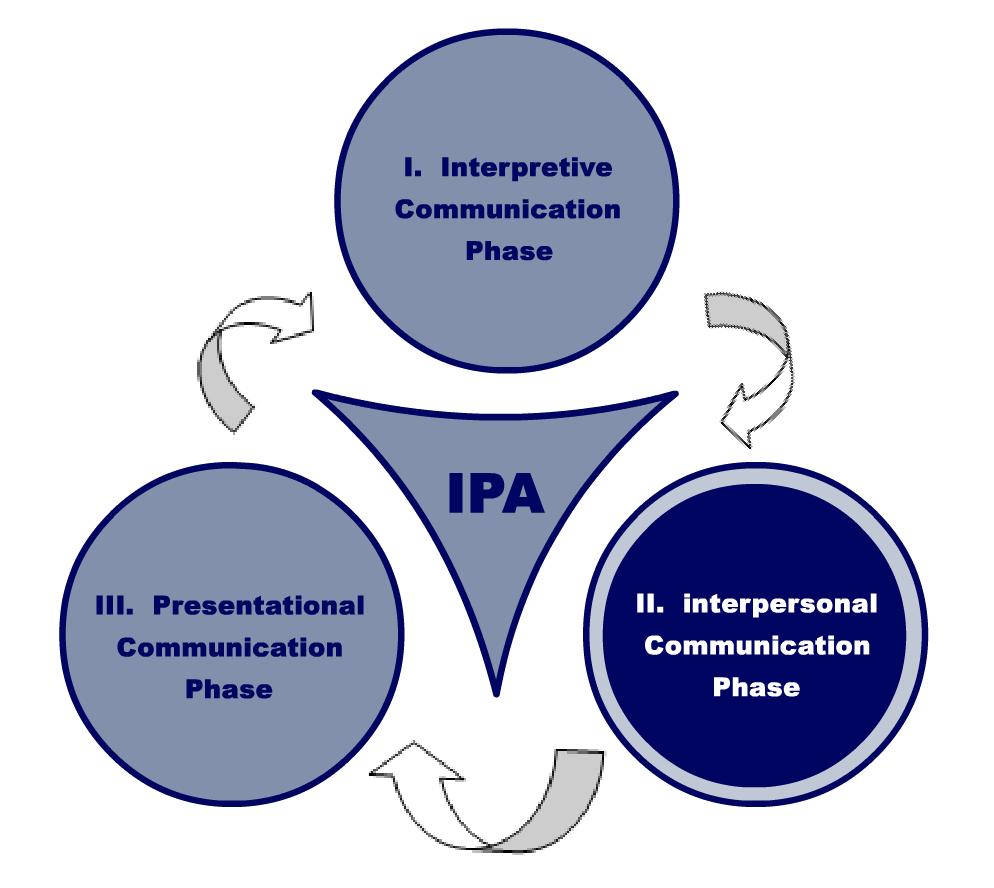

Why does the IPA offer a great potential for CBI? The IPA model provides opportunities for students to demonstrate their ability to communicate around a specific theme across these three modes of communication while constantly having the opportunity to receive feedback and improve. One core feature of the IPA, a feature we think is also key to any assessment model for CBI, is its emphasis on a “cyclical approach” to assessment, which combines continuous modeling, practice, performance, and feedback. A “feedback loop,” a key component of the framework, helps provide continuous feedback to learners throughout the assessment process (Glisan et al., 2003). For example, students receive feedback from the teacher on their performance on the interpretive task before they start on the next task. After completing the second task, they again receive feedback before continuing on to complete the cycle. The presentational task provides more opportunities for feedback as students are engaged in preparing for the task (via drafts on which students receive feedback from the teacher and possibly peers) and after they complete the task. Another feature of the IPA that is powerful for CBI is the use of authentic texts (Tedick, 2003) for the interpretive task. Using authentic texts that were originally created for native speakers of the target language is not easy for learners with lower proficiency levels and may present some challenges that must be addressed and resolved. When working with authentic texts, teachers are faced with the difficulty of identifying textual materials that are appropriate linguistically (texts that match the proficiency level of the students or that are just a little above) while challenging enough cognitively (texts that contain content appropriate for the age/maturity level). The IPA provides a great tool to guide teachers in the difficult process of selecting authentic and appropriate texts. For the interpretive task, be it listening/viewing or reading, the selection of authentic texts must vary depending on what needs to be assessed at the specific level the students are at. For the novice level, where assessment should focus on students’ identification of key words and main ideas, selected texts should not be too lengthy and their content should be contextualized enough so that learners can use their background knowledge and/or experience as a support (e.g., TV or short radio programs, commercials, songs, letters or email correspondence, etc.) (Glisan et al, 2003). At the intermediate level, where assessment is most concerned with the identification of key ideas and supporting details, text selection should include narratives, short stories, information rich texts, and so forth on topics of interest to students. The texts should also include cultural content related to the target culture (e.g., segments of appropriate TV programs such as soap operas, interviews, magazine articles, etc.) (Glisan et al., 2003). Finally, at the pre-advanced level, where assessment is predominantly concerned with the identification of main ideas and supporting details as well as the identification of varied perspectives on a given topic and the ability to make inferences, selected texts should reflect a higher degree of complexity: they should be longer, reflect more complex discourse, and should cover a wide range of topics from personal to those of general interest (the text types may be the same as for the intermediate level but the task should be more complex and demanding of students) (Glisan et al., 2003). The selection of authentic and appropriate texts is key to CBI as it naturally provides a context in which students can focus both on content and linguistic features simultaneously. Another great feature of the IPA is its focus on the creation of authentic tasks (Tedick, 2003) for students to engage in. The IPA model offers opportunities for language teachers to create “open-ended” tasks that allow students to be very creative (e.g., the creation of a video project for the presentational task). The more authentic the task (and the more real the audience and purpose), the better. Finally, the IPA is especially powerful for CBI because it involves the assessment of language as it is used in the three communicative modes. Although interpretive and presentational modes are commonly assessed within CBI, the interpersonal mode is rarely, if ever, assessed, and the IPA provides a framework for all three to be integrated meaningfully within the CBI curricular unit and within the assessment tasks for that unit. How can the IPA be adapted to be used successfully with CBI? We have identified at least four major challenges with the IPA model if it is to be used successfully in CBI contexts. The first challenge deals with the role of the thematic context that is developed for the IPA. In the IPA framework, the assessment tasks are to be developed around a general theme which provides the context for the tasks. According to Glisan et al. (2003), the theme need not be connected to the curriculum that the teacher follows for the class and indeed might serve as a departure from the regular curriculum. This allows for maximum flexibility with the IPA—that is, it can be “plugged into” an existing curriculum relatively easily. This would not be the case in CBI. Instead, in order to work effectively within CBI, the overarching theme that is selected for the IPA must be parallel to the overarching theme that guides a curriculum unit for CBI. This means that the IPA for CBI must serve as a logical extension of the content that has been covered during the course of a curricular unit. This would also allow for flexibility within the CBI curriculum. The IPA could occur at the end of a curricular unit (as a summative assessment involving the three IPA tasks) or might be integrated within a curricular unit, with the three IPA tasks being assigned at different points throughout the unit. The second challenge, directly related to the first, has to do with the fact that the IPA is fundamentally a framework for assessing language, not content. Even though the three IPA tasks are to be designed around a theme, the principal aim of the IPA remains exclusively focused on the assessment of language. A content or cultural theme is simply used to provide a context for language use. The assessment of content knowledge is still considered secondary (if it’s considered at all). This focus on language can be clearly seen in the IPA rubrics provided in the manual (Glisan et al., 2003). For example, the rubrics for the presentational mode include categories such as language function (i.e., the types of communicative tasks the student can handle), text type (i.e., the organization and discourse quality of the oral or written text produced by the student), and impact (including vocabulary, comprehensibility to the audience, and language control). These rubrics make no mention of any categories that target content knowledge. A similar pattern occurs for the interpretive and interpersonal rubrics that are offered in the manual. Thus, if the IPA is to be used for CBI, its focus must be rethought so that both content and language are assessed based on the tasks required and the rubrics used for evaluating student performance. A third challenge relates to the recommended order of the second and third tasks within the IPA assessment cycle. The IPA cycle begins with an interpretive task, which we agree is highly appropriate given that the interpretive task provides the necessary background on the content theme of the assessment (in the form of a written or oral text such as a story or a news broadcast). According to Glisan and colleagues (2003), the next task that should come in the cycle is the interpersonal task—a task where learners are to engage in spontaneous, face-to-face communication that involves negotiation of meaning. We would argue that this is problematic. Authentic interpersonal communication is difficult to achieve, particularly with learners having lower proficiency levels, because it requires spontaneous interaction. Brown and Yule (1983) argued decades ago that interactional discourse (parallel to interpersonal communication) cannot be taught and that language teachers should focus on the teaching of transactional discourse (parallel to the presentational mode), because it is by engaging in the preparation and rehearsal of transactional discourse that students acquire the skills they need to engage in interactional discourse (Brown & Yule, 1983). If students have an opportunity to complete the presentational task before the interpersonal task, they will have more content knowledge to draw on and will have practiced and presented the structures and vocabulary they need to engage in the interpersonal task. Having the tasks in this order—interpretive, presentational, interpersonal—is especially important for learners with low levels of proficiency but is valuable as well for more advanced learners. Finally, the last challenge with the original IPA framework that must be addressed is that it does not reflect the necessity of integrating other standards within the 5 C’s of the national Standards for Foreign Language Learning. The focus is simply on the three standards that relate to the communication goal. Although it is possible to incorporate the other standards, the possibility is not mentioned at all in the IPA manual. The following figure represents an attempt at illustrating what the IPA model would look like after having been optimized for CBI:

In this illustration, content serves as the core around which language is used to carry out the three communicative modes, beginning with the interpretive mode, followed by the presentational mode, and finally the interpersonal mode. The five C’s serve as the backdrop for developing the tasks that students perform in the IPA. Thus, for example, in a unit on water conservation (connections goal) for a high school French III class, students read a webpage from the Belgian government titled “Comment préserver l’eau à la maison?” (How to conserve water at home) (interpretive mode, communication goal) This text incorporates cultural products and practices and reflects cultural perspectives (cultures goal). The distinct cultural products, practices and perspectives are used to make comparisons to similar products, practices, and perspectives in the U.S. (comparisons goal) as students in pairs complete a Venn diagram to compare/contrast these cultural products, practices and perspectives (interpersonal mode, communication goal). The final, culminating performance task of the unit is a skit or children’s book that students create (presentational mode, communications goal) and present to elementary students at a nearby French immersion school (communities goal). Conclusion The IPA has powerful potential for CBI as long as a number of modifications are made to the model. We have described in this piece what we consider to be four major challenges to the original IPA model for use with CBI—(1) the need to provide a content focus, not to use content simply as a contextual frame for the IPA, (2) the need to develop a framework for assessing both content and language, not just language, (3) the need to create a different sequence for IPA tasks, i.e., interpretive, presentational, interpersonal vs. interpretive, interpersonal, presentational, and finally, (4) the need to maximize the use of the five goals of the national standards as the backdrop for the IPA rather than focusing on the communications goal alone. References: Beckett, G.H. & Slater, T. (2005). The project framework: A tool for language, content, and skills integration. ELT Journal, 59(2), 108-116. Brown, & Yule (1983). Teaching the spoken language. Cambridge University Press. Glisan, E.W., Adair-Hauck, B., Koda, K., Sandrock, S.P., & Swender, E. (2003). ACTFL integrated performance assessment. Yonkers, NY: American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. Stoller, F. (2002). Content-Based Instruction: A Shell for Language Teaching or a Framework for Strategic Language and Content Learning?'' TESOL: Plenary Address, Salt Lake City, UT. Tedick, D. (2003) "CAPRII: Key Concepts to Support Standards-Based and Content-Based Second Language Instruction." [online] /cobaltt/modules/strategies/caprii.html

|

||||||||||||