Building a Syllabus: Backward Design for Syllabus Design

Backward design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) is a framework for syllabus design. Traditionally syllabus design has been approached in a forward design manner, meaning that content is considered first. Content-centered syllabi are what many people are used to—you have likely been handed such syllabi as a student and as an instructor. Content-centered syllabi start with a list of topics to be covered (not uncommonly based on textbook chapters and the way in which they are sequenced) over the academic term, then learning activities are selected, assignments and tests are developed around these learning activities, and finally connections are drawn to the learning objectives. This approach to syllabus design focuses on what the instructor wants to do and thus makes it instructor centered.

With backward design instructors start creating a syllabus by thinking about who their students are and what they want them to know and be able to do at the end of the course and then work backward from there. The backward design framework, despite its name, is actually quite forward thinking in that it promotes intentional planning to create assessments and determine learning activities and course materials needed to support the desired learning objectives. This approach to syllabus design is student-centered.

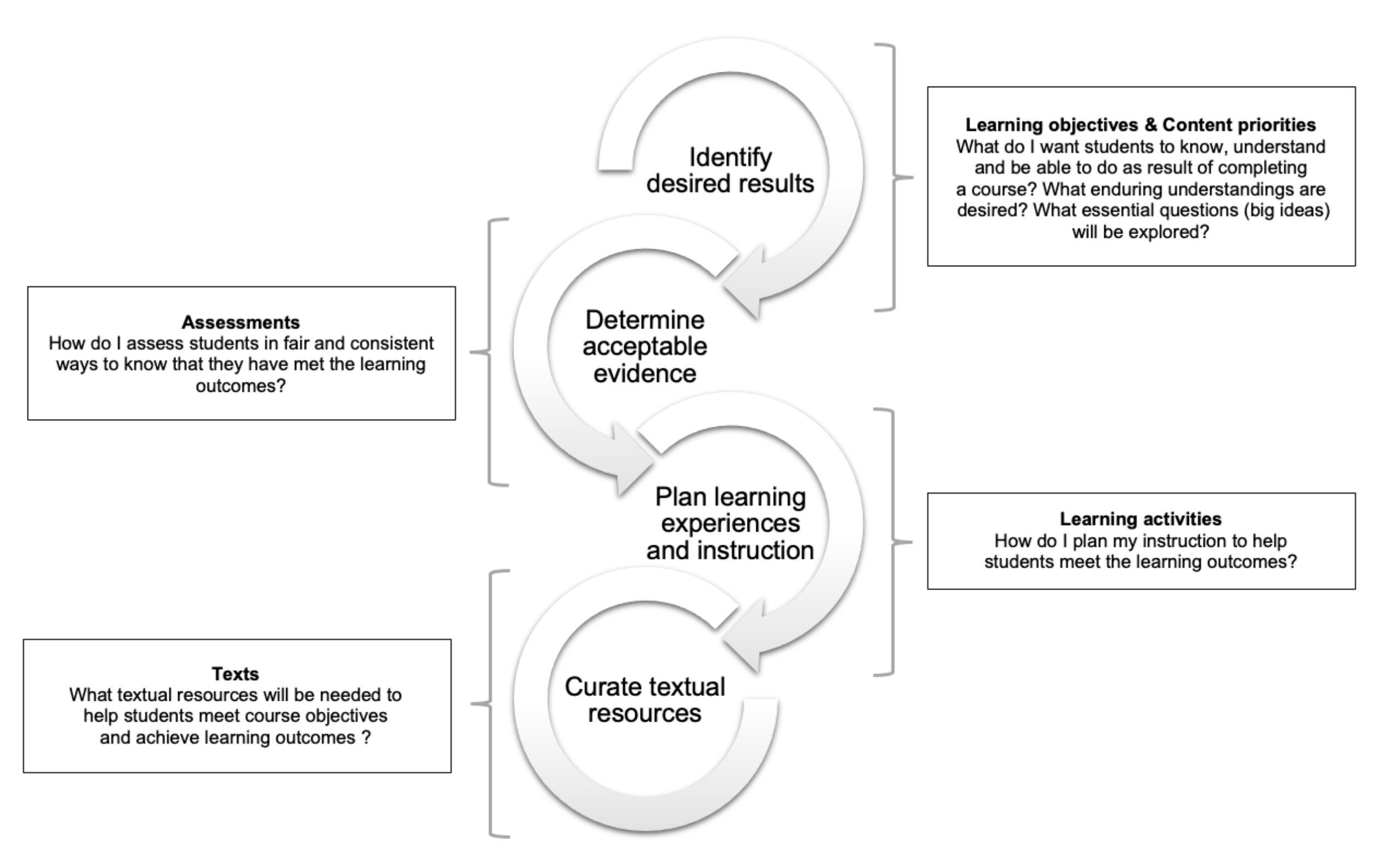

The three stages of backward design represented in Figure 1 include: (1) identifying desired results through use of essential questions that will help students develop and deepen understandings and through articulation of learning objectives; (2) determining acceptable evidence that students have achieved the learning objectives through formative and summative assessments; and (3) planning learning experiences and instruction. A fourth stage is also included in Figure 1: curating textual resources that will help students provide evidence that they have met the course goals and learning objectives. The model does not prescribe a specific instructional method or approach to design learning activities; any instructional method or approach is acceptable as long as it supports student learning consistent with the stated course goals and learning objectives (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

Adopting a backward design approach to syllabus design has several benefits. First, as previously mentioned, it encourages instructors to think intentionally about how in-class activities and assessments will ensure that the course goals and objectives are met. In addition, backward design helps instructors determine what material is necessary for students to meet the stated course objectives and therefore makes it easier to decide what content to include and what content to put aside. Another benefit of using backward design is that students appreciate the transparency and clarity that comes with knowing what is expected of them. Finally, adopting a backward design approach can have a positive impact on student learning and motivation (Hodaeian & Biria, 2015; Korotchenko et al., 2015).

Backward design can be an iterative process. As you develop your assessments, you may realize that your learning objectives must be refined. Similarly, as you plan your learning experiences, you may come up with original ideas on how to assess students, which may lead you to change your assessment plan.

Learning Activity:

Part 1: Below you will find learning objectives for an elementary Spanish course as well as unit-level learning objectives related to buying food at a convenience store. Read through both sets of objectives and then move on to Part 2.

Upon completing Elementary Spanish I, students will be able to demonstrate their developing ability to:

- Understand cultural products, practices, and perspectives of the Spanish-speaking world and relate them to their own culture(s);

- Understand and use a range of language forms appropriately and accurately in spoken and written contexts;

- Analyze and interpret the cultural content of multimodal texts of various genres;

- Identify and explain connections that exist between the language and other modes used in texts and the cultural information and ideas expressed in those texts; and

- Reflect on their own language learning processes.

Student learning objectives: At the end of this unit, students will be able to

- Understand the purpose of a simple conversation to buy food in a convenience store in the United States and Mexico (course SLO #1)

- Identify and use the key features of a simple conversation to buy food in a convenience store in Mexico (course SLO #2)

- Develop awareness of how the relationship between the participants, the focus of the conversation, the modality of the communication impact a simple conversation to buy food in a convenience store (course SLO # 3 & 4)

- Identify the key stages of a simple conversation to buy food in a convenience store in the United States and Mexico (course SLO #4)

- Students reflect on their shopping experiences in Nogales, Mexico (course SLO #5)

Part 2: Now look at the activities and assessment listed for a lesson that focuses on unit-level learning objective #1. How do the activities help to meet this objective?

Unit SLO 1: Understand the purpose of a simple conversation to buy food in a convenience store in the United States and Mexico

Lesson Activities

- Guided class conversation about shopping experiences in their L1 and the purpose of using language and other modes in a store.

- Students visit a local convenience store and gather information on exchanges that take place between customers and vendor in English: structure, purpose, topic, relationship between people.

- Teacher leads conversation to present and use Spanish vocabulary related to food and quantities

- Students watch several short conversations in Spanish that takes place at a mercado. Students compare this conversation to the one they observed for activity 2.

- Together teacher and students construct an explanation of how simple conversations to buy food unfold.

- Teacher shows how conversation develops in pairs of turns and highlights how they are connected.

- Formative Assessment: Together students map out the stages of the genre with key expressions and structures in Spanish associated with each of them and then get to practice these in short dialogues.

Part 3: Choose a second unit-level learning objective and come up with a list of classroom activities and a formative or summative assessment. Share your ideas with an experienced LPD at your institution or one of your professors. How can your ideas be improved?